This tissue is classified in:

- Loose connective tissue (sometimes called areolar tissue)

- Reticular connective tissue

- Elastic connective tissue

- Dense connective tissue

Loose connective tissue

This tissue is characterized by the presence of numerous different cells and by a scarcely dense amorphous substance lacking in fibers. This makes it difficult to stain it with common histological dyes.

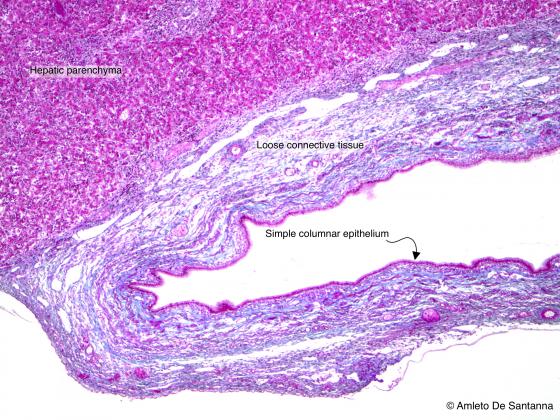

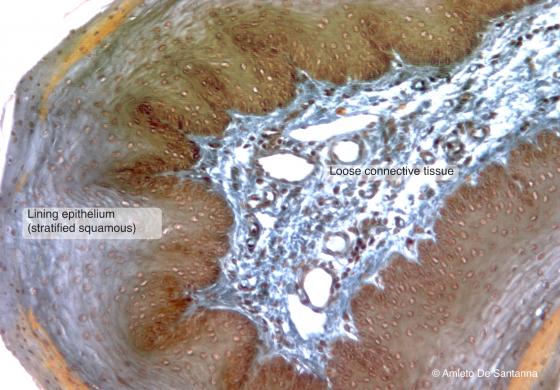

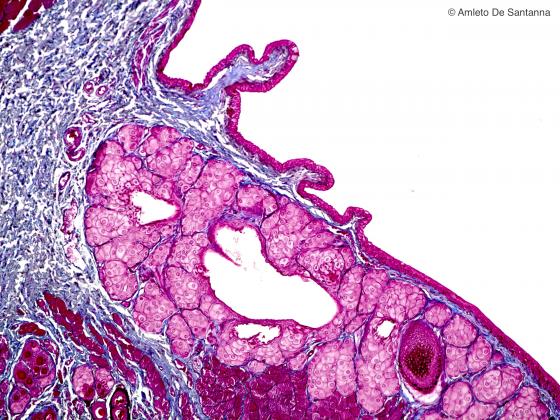

Figure C4. Human gallbladder. Loose connective tissue. Part of the liver and longitudinal section of the gallbladder where you can easily see the thick layer of loose connective tissue. Mallory-Azan X40

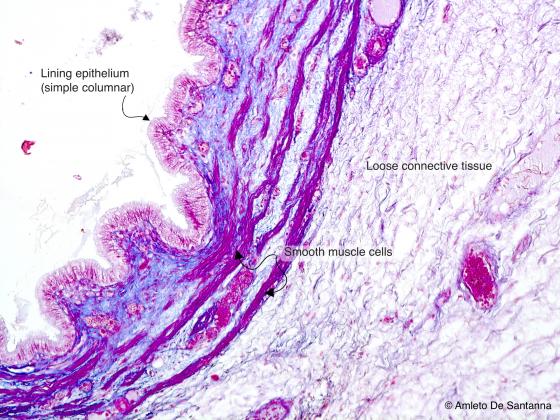

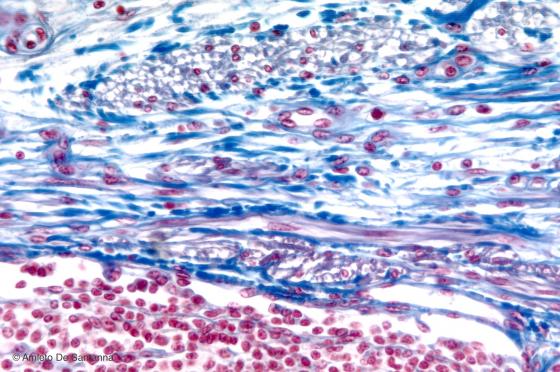

Figure C5. Human gallbladder. In this micrograph, you can see the lining epithelium, the basement membrane and appreciable fascicles of smooth muscular tissue (stained red-purple) sinked into loose connective tissue. The loose connective tissue is easily identified because of the paucity of fibers, the large amount of extracellular matrix, the large number of cells and the blood vessels and nerve fibers that cross it. Mallory-Azan X100

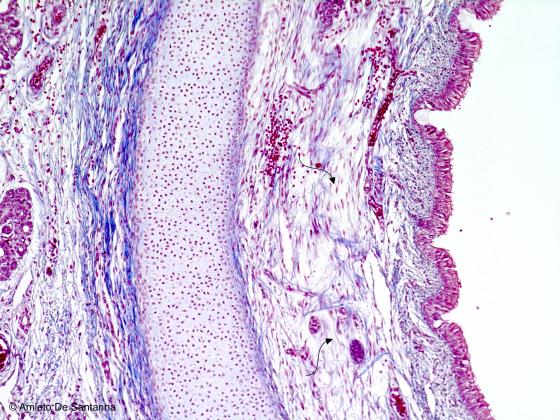

Figure C6. Human fetal trachea. Loose connective tissue of the mucosa of the trachea (arrows). Mallory-Azan X25

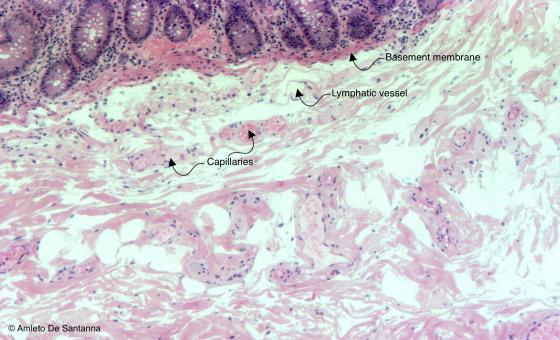

Figure C7. Human large intestine: cecum. Loose connective tissue. H&E X64

Figure C8. Rabbit esophagus. Loose connective tissue. The esophagus submucosa is made of loose connective tissue. Nonetheless, the large number of cells and blood vessels, you can see a large amount of both collagen and elastic fibers that give the esophagus its elastic property. Ignesti X100

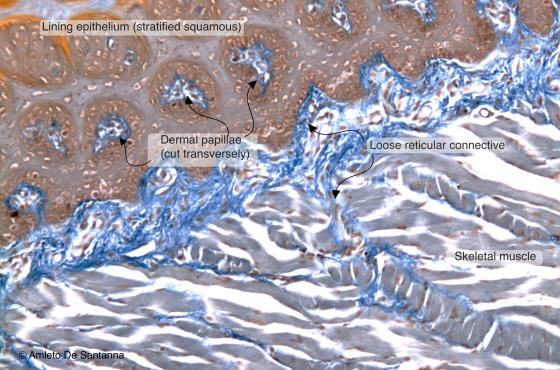

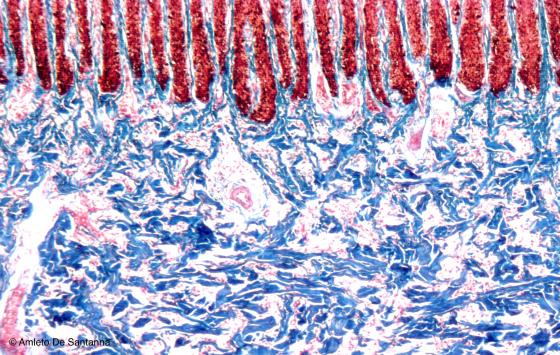

Figure C9. Rabbit tongue. Loose connective tissue. The tongue is lined by squamous stratified epithelium that leans on a basement membrane. Below this basement membrane, there is a network of collagen fibers, stained blue. Ignesti X100

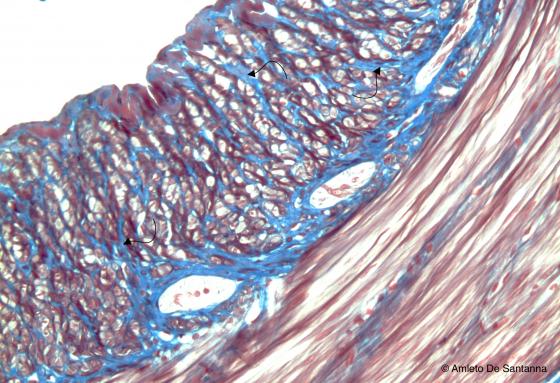

Figure C10. Mouse intestine. A thick connective network (arrows, stained blue) wraps the muscular cell fibers of the intestine. Mallory-Azan X100

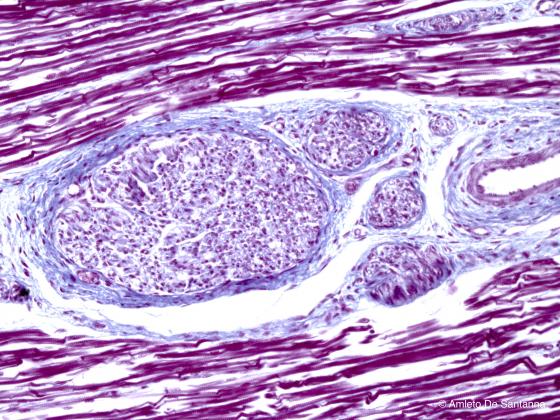

Figure C11. Human muscular tissue. Nerve fascicles enclosed in connective tissue (stained blue) Mallory-Azan X200

Reticular connective tissue

This tissue is packed with reticular fibers composed of type III collagen. Although these fibers are composed of collagen, due to their different organization, size, function and strong affinity for metallic silver (they are also known as argyrophilic fibers) they have kept their original name, namely, reticular fibers or reticulum fibers.

It seems like their major affinity for silver staining techniques, which is the base for Bielschowsky’s method for reticular fibers, is to be connected to fiber conformation and their surrounding matrix, rather than to the biochemical characteristics of fiber constituents. From a histological point of view, the only real difference between these and other collagen fibers is their organization: the latter are organized in bundles, while reticular fibers are isolated and generally form a thin meshwork. These fibers surround the single muscle fibers and the peripheral nerve fibers, in order to isolate them from each other. They associate to the basal lamina, underneath epithelia, surround the adipocytes and compose the thin meshwork that constitutes the connective stroma of lymphatic organs and large glands, both exocrine and endocrine.

In embryonic life, during the transformation from mesenchymal to connective tissue, reticular fibers appear first. Subsequently collagen fibers substitute most of them.

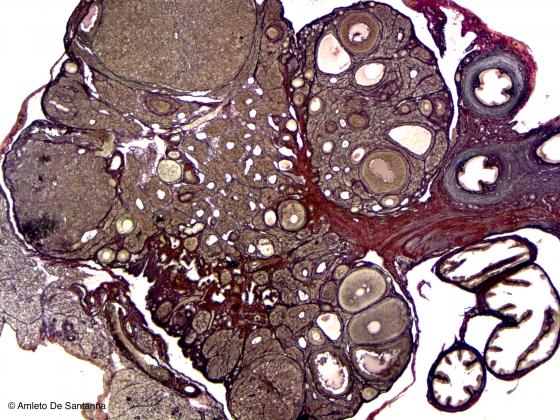

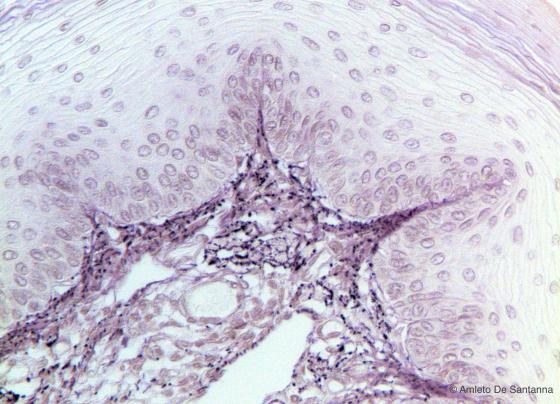

Figure C12. Mouse ovary. Reticular connective tissue that spreads to the whole ovarian stroma and gets thicker in the basement membranes. Bielschowsky X25

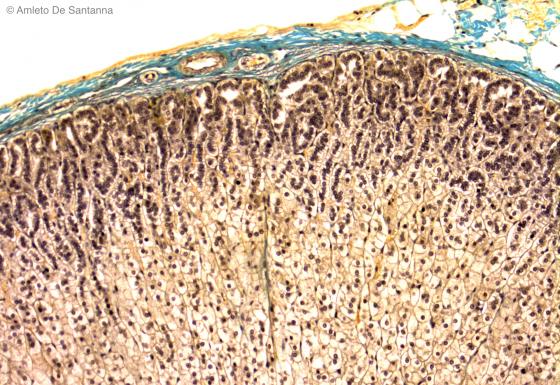

Figure C13. Mouse ovary. Reticular connective tissue stained black by silver precipitate. The reticular fibers are defined argyrophilic because of their affinity to silver salts. Bielschowsky X64

Figure C14. Mouse ovary at higher magnification. The reticular fibers are thicker below the epithelium of the follicles in order to provide a strong basement to epithelial cells but allowing, at the same time, the passage of blood vessels for trophic function. Bielschowsky X100

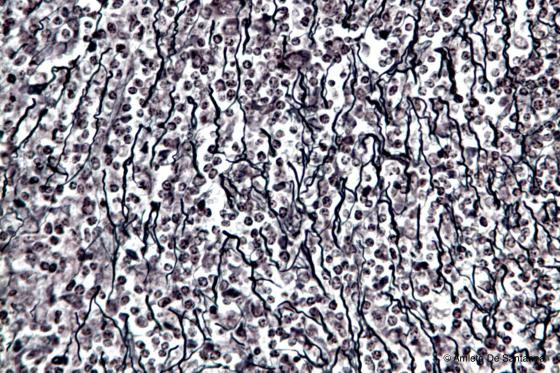

Figure C15. Mouse uterine tubes. Reticular fibers, stained black, make up the connective network that surrounds the smooth muscle cells of the muscularis externa of the uterine tubes. Bielschowsky X200

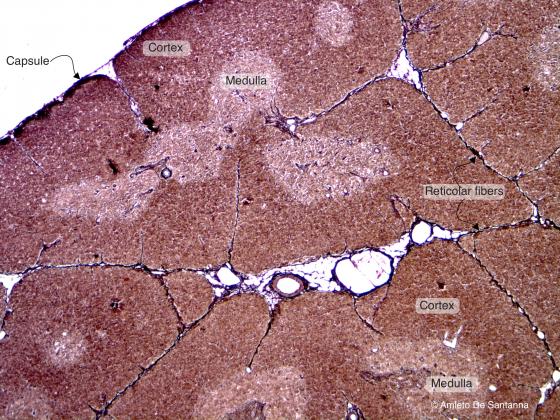

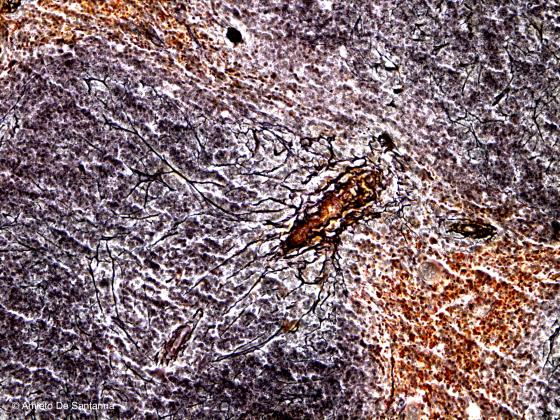

Figure C16. Mouse thymus. Reticular fibers that outline the thymus architecture and that enclose a few blood vessels. Bielschowsky X100

Figure C17. Mouse thymus at higher magnification. Thin network of connective reticular fibers that is obvious in the medulla. Bielschowsky X100

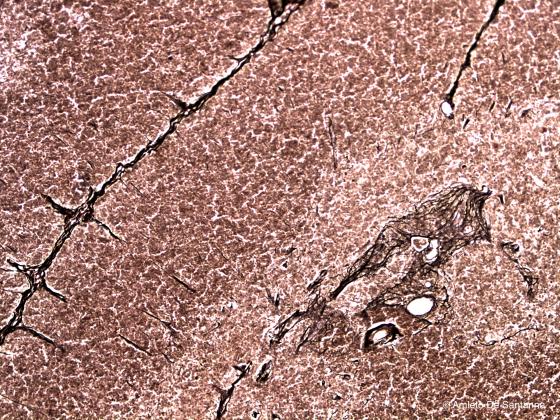

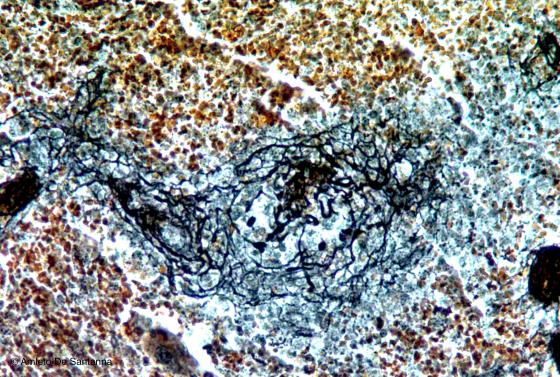

Figure C18. Mouse spleen. Thick network of reticular fibers that enclose a capillary. Bielschowsky X100

Figure C19. Human spleen. Network of connective reticular fibers that forms the connective support of the spleen. Gomori for reticular fibers X200

Figure C20. Human spleen. Connective reticular fibers that enclose a small capillary. Bielschowsky X200

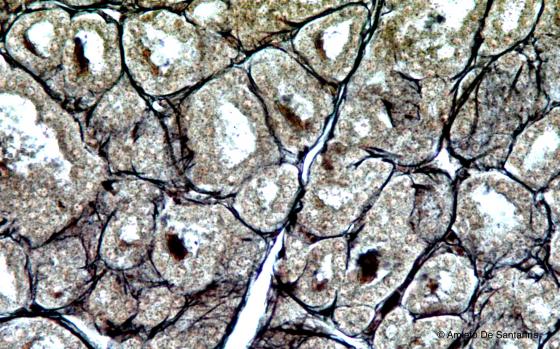

Figure C21. Human thyroid. The reticular fibers form a thin reticular network that encloses the follicles of the thyroid. Bielschowsky X200

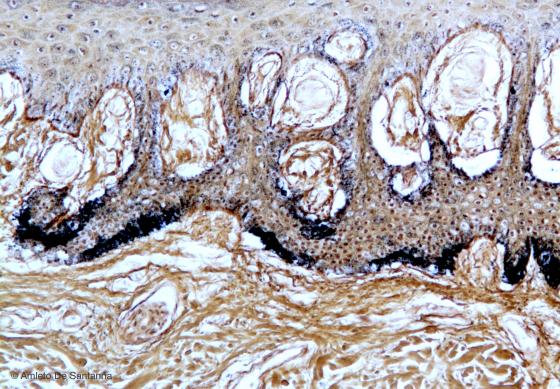

Figure C22. Skin of human palm, transverse section. Collagen reticular fibers, stained black by metallic silver, that contribute to formation of the basement membrane. Bielschowsky X100

Elastic connective tissue

The different structures that compose an organism often have to react to mechanical impulses or perform slip and slide functions. Connective tissue has to follow this movement, and to do so it needs an elastic structure, able to satisfy such impulses. However, once the impulse is over, the structure must be able to return to its original shape and size, without deformations.

This type of tissue is called elastic. Elastic connective tissue is composed of non-birefringent fibers, different from the ones composing collagen connective tissue. These fibers are formed by elastin, amorphous substance and fibrillin.

The structure of connective tissue can be organized in parallel fibers (e.g. the nuchal ligament of ruminants, human spine ligaments and tendons) or in fibers, in larger or smaller amounts, scattered in collagen (epiglottis, external ear, urinary bladder). Arterial walls do not present fibers and elastin is composed of fenestrated lamellae called elastic membranes.

At a macroscopic level, elastic connective tissue can be easily distinguished by the yellowish color given by elastin; instead, from a microscopic point of view it can be detected only with selective dyes made with resorcin-fuchsin (Weigert’s) or aldehyde-fuchsin (Halmi’s) that provide this tissue with an intense, dark violet color.

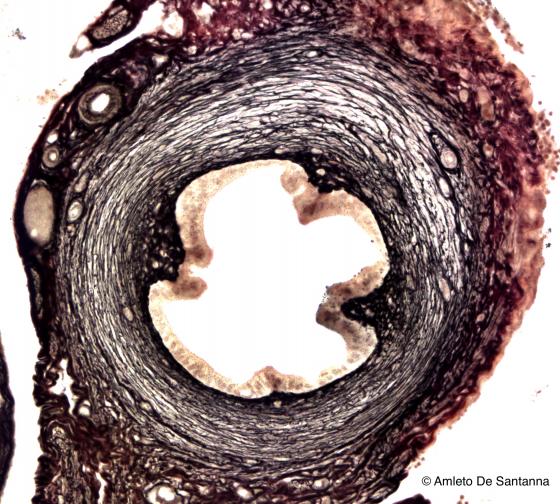

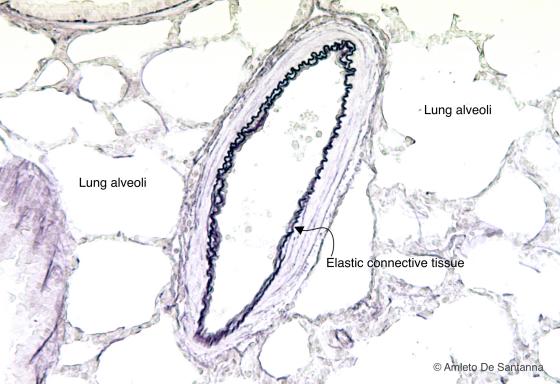

Figure C23. Rabbit lung. Elastic lamellae stained black-purple, of the tunica media of a lung artery. Weigert X160

Figure C24. Guinea-pig brain. Section of an artery where you can easily see the internal elastic membrane, not stained. Bodian-Protargolo X400

Figure C25. Rabbit lung. Elastic fibers enclosing an artery in the lung. You can see the characteristic sinusoidal run of the fibers forming the elastic lamellae. With this staining technique the nuclei, the cytoplasm and the extracellular matrix are poorly stained. Weigert X100

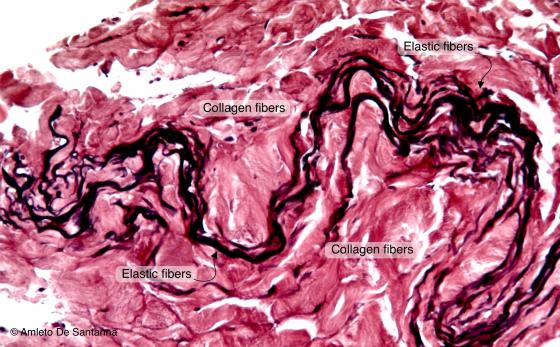

Figure C26. Human artery. Selective staining that highlight the elastic fibers of the tunica media (stained black). You can easily see the internal elastic membrane. In order to have a better contrast, the sample was stained also with H&E. Weigert/H&E X100

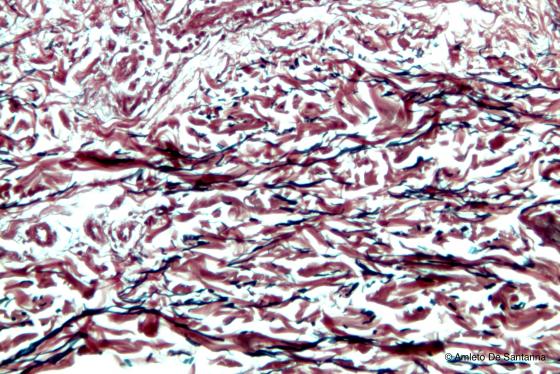

Figure C27. Human skin. The elastic fibers, stained black-purple, are wavy because they were fixed in resting state. In order to have a better contrast, the sample was stained also with H&E. Weigert/H&E X100

Figure C28. Human skin. Elastic fibers of the dermis, stained black, with their characteristic sinusoidal run, in a longitudinal view. The collagen fibers are stained pink. Weigert/H&E X100

Figure C29. Rabbit esophagus. Elastic fibers (stained dark purple, sectioned transversely) present in the connective tissue of the mucosa. Weigert X100

Dense connective tissue

This tissue is marked by multiple fibers made of type I collagen. They are disposed in bundles (that can be even very thick), immersed in amorphous substance and oriented towards various directions. They can be parallel (tendons), crossed (cornea) or interwoven fibers (dermis). There are fewer cells, compared to loose connective tissue. Dense and loose connective tissues do not have precise borders between them when they are in contact.

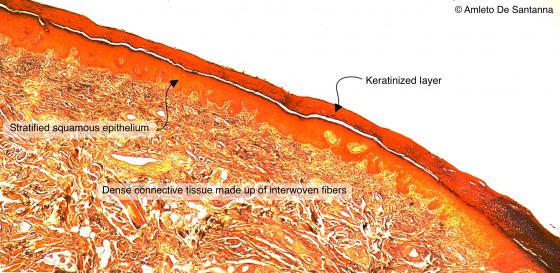

Figure C30. Human skin. Dense connective tissue made up of interwoven fibers characteristic of the dermis. Ignesti X25

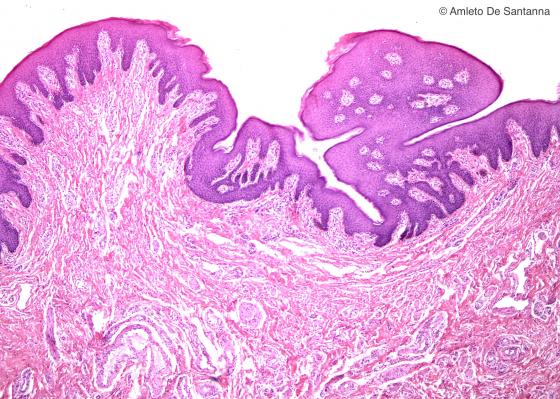

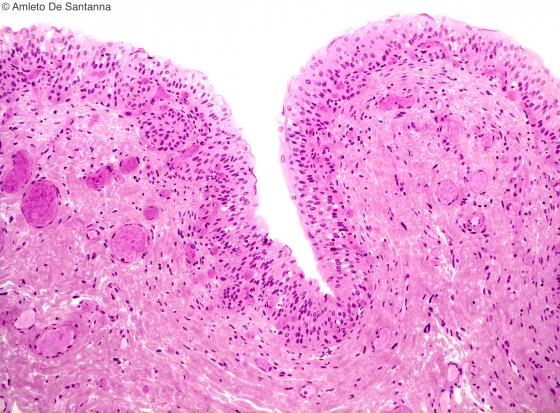

Figure C31. Human prepuce. Dense connective tissue made up of interwoven fibers. H&E X40

Figure C32. Human eyelid. Dense connective tissue of the eyelid (tarsal plate) made up of interwoven fibers, stained light blue-gray. Mallory-Azan X40

Figure C33. Human urinary bladder. Section of dense connective tissue mixed with smooth muscle fibers. H&E X100

Figure C34. Rabbit surrenal gland. A capsular dense connective tissue, stained light blue-green, encloses the surrenal gland. Ignesti X100

Figure C35. Pig lymph node. Irregular capsular dense connective tissue that encloses the lymph node. Mallory-Azan X64

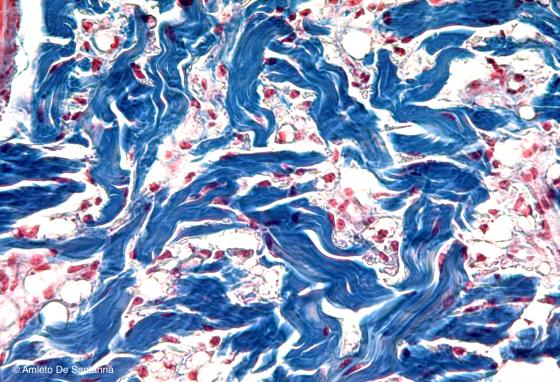

Figure C36. Whale skin. Dense connective tissue of the dermis made up of interwoven fibers. These fibers, in order to oppose a greater resistance, are thick, interwoven and rich in collagen. Mallory-Azan X64

Figure C37. Whale skin. Dermis at higher magnification where you can see, in the intricate weave of connective fibers, adipose tissue, both white (unilocular) and brown (multilocular). This particular organization of the dermis of marine mammals is called blubber. Mallory-Azan X200

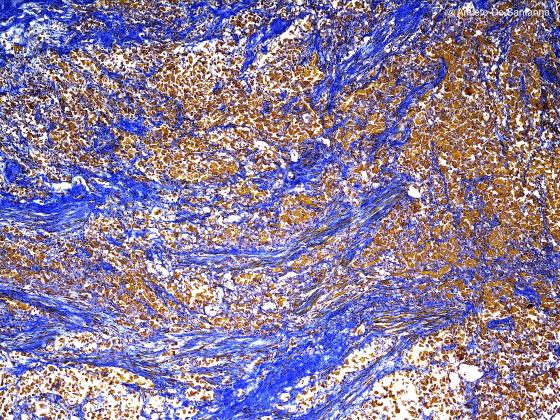

Figure C38. Human prostate gland. Dense connective tissue made up of interwoven fibers, stained light blue, and interspersed smooth muscle fibers, stained brown. Ignesti X40

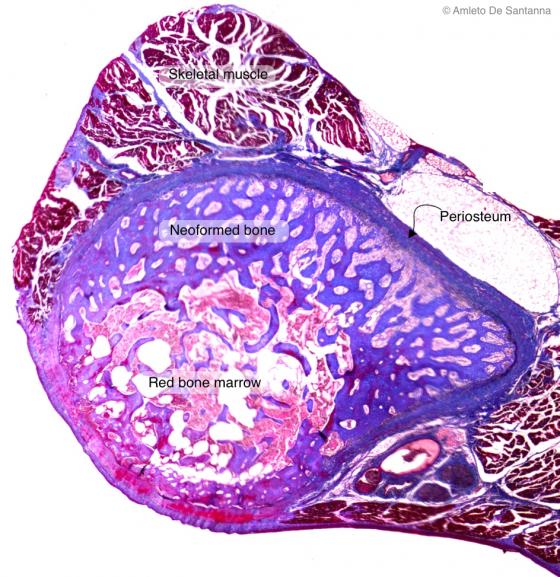

Figure C39. Human fetal rib during the process of bone formation. Dense irregular connective tissue of the periosteum. Mallory-Azan X40

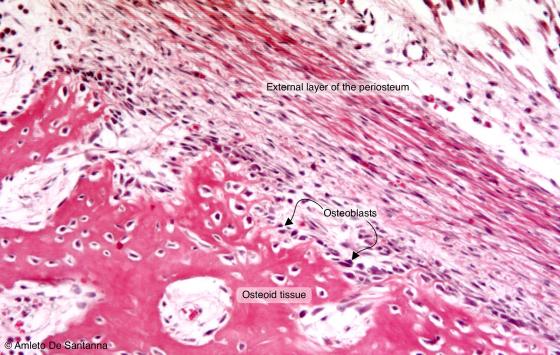

Figure C40. Foot of human embryo. The dense connective tissue that surrounds the bone is named periosteum. It can be identified by the dense and irregular fibers (rich in collagen and therefore stained red-orange) present in the external layer. In the internal layer, there are osteoblasts that are directly in contact with the bone and responsible of its growth during fetal life and development. In the adult, in case of bone fracture, the perisiosteum is responsible for the formation of the bony callus. H&E X100

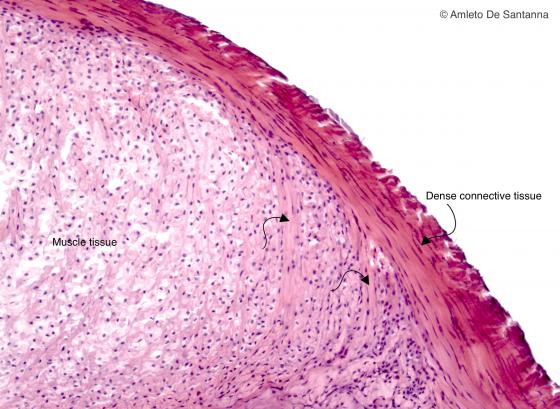

Figure C41. Human myotendinous junction. Dense connective tissue made of parallel fibers. The connective fibers run regular and parallel to resist effectively to traction. You can see bundles of connective tissue (arrows) that enter the muscle tissue to anchor the tendon to the muscle. H&E X25

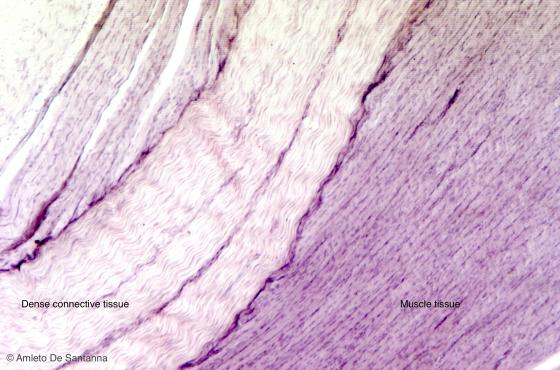

Figure C42. Human tendon. Dense connective tissue made of parallel fibers. At rest, the connective parallel fibers run in a slightly sinusoidal way because of the high content in elastic fibers. H&E X64

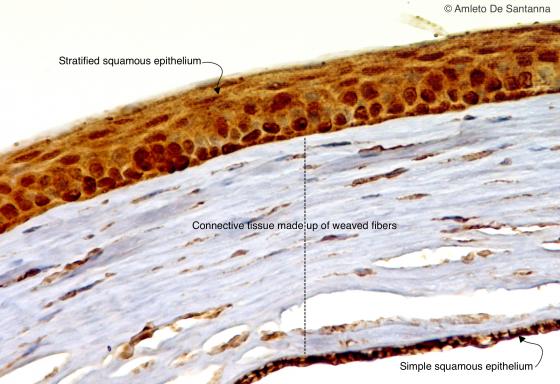

Figure C43. Mouse eye. Cornea. Regular dense connective tissue made up of crossed bundles (dotted line). In this kind of connective tissue, each fiber layer is positioned orthogonally to the one below. Thanks to this organization of the fibers, the tissue is clear and transparent allowing the light to run through it without aberrations. HRP-E X200